The formation of the SNP can be traced right back to 1934 the Party was formed from a combination of the Scottish Party and the National Party of Scotland. John MacCormick was the leading figure behind its inception. He intended to create a unified front within Scotland, as the belief was that such strength would increase the popularity of the party. The SNP did not initially seek complete independence; on the contrary, the main goal of Mr MacCormick was to secure a limited amount of autonomy within the United Kingdom. This position was not embraced for very long, and soon after the inception of the party, the primary focus returned to complete independence. One of the main issues which gripped with Scottish Nationalist Party from the 1930s well through to the 1970s was an ongoing debate as to whether the SNP should strive for complete independence or a political devolution from the United Kingdom. This caused Mr MacCormick to leave the party in 1942 to be succeeded by Professor Douglas Young who proved to be a more radical figure; perhaps best known for urging Scots to refuse conscription during the Second World War. Another issue that the party encountered was that when Mr MacCormick left and established the non-partisan Scottish Covenant Association, many SNP members followed suit. This deprived the party of much of its power, and for a time, the Scottish Covenant Association represented a potent political threat.

One of the main issues which gripped with Scottish Nationalist Party from the 1930s well through to the 1970s was an ongoing debate as to whether the SNP should strive for complete independence or a political devolution from the United Kingdom. This caused Mr MacCormick to leave the party in 1942 to be succeeded by Professor Douglas Young who proved to be a more radical figure; perhaps best known for urging Scots to refuse conscription during the Second World War. Another issue that the party encountered was that when Mr MacCormick left and established the non-partisan Scottish Covenant Association, many SNP members followed suit. This deprived the party of much of its power, and for a time, the Scottish Covenant Association represented a potent political threat.

It was not until 1945 that the Scottish Nationalist Party won its first seat in parliament and even this position did not last for very long, and it would be another 22 years before the Icon that was Winnie Ewing won in Hamilton, and continuing fairly low levels of support further defined the post-war period and well into the 1950s. Notwithstanding the rather marred years during the 1950s, the SNP began to become more organised throughout the 1960s. A growing number of recognised branches throughout Scotland were a direct result. Many feel that the attitude of the organisation throughout the decade was summarised quite well with a statement made by political figure Winnie Ewing. She famously stated “Stop the world. Scotland wants to get on.”

This observation was reinforced when the SNP garnered no less than 40 per cent of votes during the 1968 Local Council Elections. However, in 1969 a massive supply of oil was found in the North Sea. And by emphasising how oil could improve the lives of average Scots, the party enjoyed pronounced success. This was highlighted in 1974 when the party held 11 parliamentary seats and enjoyed more than 30 per cent of all Scottish votes.

During the first half of the 1970s, the Scottish Nationalist Party again experienced slight fragmentation such as when members left in 1973 to form the Labour Party of Scotland. However, this movement soon faded and most returned to the SNP. However, in Westminster, the minority Labour government could only operate with the support of MPs from the SNP and Plaid Cymru. Their reward for this support was the open discussion of devolution In 1969, a Royal Commission on the Constitution was set up to look at the structures of the Constitution of the United Kingdom. Various models of devolution were considered and rejected. Then in the mid-1970s, the pressure for reform grew. The Labour government of the time put forward a law to create a Scottish Assembly. The Scotland Act 1978 became law on 31 July 1978 The Act required that 40% of the Scottish electorate (not just of those who voted) had to support the Act for it to come into force. Although the devolution scheme was supported by 52% of those voting. This amounted to only 33% of the electorate so the scheme could not go ahead. Following this, there was a vote of no confidence in the Labour government, which fell and was subsequently defeated at a general election in May 1979. The Act was “repealed” (cancelled) in June 1979. When the voting failed to achieve the required 40% of the Scottish electorate to endorse an independent Scottish parliament, this signalled a slight decline in terms of confidence, and subsequently, several factions such as the 79 Group and Siol nan Gaidheal formed. During this time the poll share of the SNP declined to 17% and only two seats in the UK parliament.

1979 also saw the election of a Tory government under Margaret Thatcher which led to the Conservative dominance of British politics until 1997. And we all know what happened to Scotland under her government. During the 80s factionalism become much less prevalent; partially due to the collapse of the Scottish Labour Party after the elections of 1979. Many former members understandably turned to the SNP. However, the party still performed poorly in both the 1983 and 1987 elections.

Leaders such as Jim Sillars claimed that the Scottish National Party needed to provide voters with reasons why independence would be beneficial. Socio-economic reforms were also given greater importance. By the end of the decade, the SNP had once again organised itself into a viable political entity. In 1987 the Scottish constitutional convention was formed meant to be a cross-party alliance to kick-start the issue of devolution. The Scottish Tory party wanted nothing to do with it and the SNP refused to take part as they felt that devolution Was not what they wanted which was full independence from Westminster, it produced its report in 1995 and some of it formed part of the basis of the scheme that was implemented after 1997. The election of Alex Salmond in 1990 highlighted that the SNP had embraced a left-of-centre social democratic stance, as this new leader was known for his wit and intelligence; his charisma boosted the popularity of the SNP throughout Scotland. The early 2000s saw the return of Alex Salmond as party leader. While progress was slow, the party garnered 35 out of a total of 129 seats within the newly formed Scottish parliament during the 1999 elections. Many previous opponents backed his candidacy, and he was elected after the 2005 general elections. While six seats were gained within the Westminster parliament, the overall voting share within the Scottish parliament fell to 17 per cent. This was offset by a resurgence during the 2007 general elections and perhaps more importantly, by the landslide victory that occurred in 2011. The SNP’s performance in 2011 was even more impressive, securing the first majority government in the history of the Scottish Parliament. Having secured that majority, Salmond pledged to hold a referendum on independence within five years. In 2012 he signed an agreement with British Prime Minister David Cameron to hold the referendum, which was ultimately scheduled for September 2014, and to pose a single simple question: “Should Scotland be an independent country?” The 2014 campaign for Scottish independence illustrates the impact that the SNP has upon politics within the United Kingdom. While the motion was ultimately defeated, party membership increased massively. During the 2015 United Kingdom general elections, the SNP garnered an incredible 56 seats out of a total of 59.

In May 2016 Nicola Sturgeon led the SNP to its third straight victory in elections for the Scottish Parliament, though the party lost its outright majority, slipping from 69 seats to 63. Sturgeon eschewed forming a coalition. Instead, she insisted that the results still mandated solo rule by the SNP, albeit as a minority government. On June 23, 2016, the majority of Scots who voted in the national referendum on British withdrawal from the European Union (“Brexit”) opted to remain within the EU. The U.K.-wide vote, however, was for Brexit, prompting Nicola Sturgeon to advocate for another referendum on Scottish independence to be held before the United Kingdom’s formal withdrawal from the EU in 2019. When the SNP lost 21 seats (falling to 35 seats) in the snap election for the U.K. House of Commons in June 2017, that devastating result was widely seen by some commentators as a rebuke of Nicola Sturgeon’s call for another vote on independence. However, the party bounced back in the early parliamentary elections that were held in December 2019, gaining 13 seats, to secure 48 seats in the House of Commons. In the May 2021 elections for the Scottish Parliament, the SNP bettered its result in the 2016 elections by one seat to reach a total of 64 seats, just one seat shy of an outright majority. The negotiating of a Brexit agreement that would be acceptable to the EU and able to win approval in Westminster proved immensely difficult and ultimately unattainable for May, who, having been forced to plead for deadline extensions for Britain’s exit date from the EU, resigned as Conservative Party leader in early June 2019. Boris Johnson, who replaced her as prime minister, won a mandate for his vision of hard Brexit in another snap parliamentary election in December. The version of Brexit that Johnson finally pushed across the finish line on January 31, 2020, was anathema for Nicola Sturgeon and deeply unpopular with most Scots, not least those in the fishing and seafood industry, who lost their crucial direct access to EU markets.

Once again, Sturgeon began to set her sights on independence, but before she could hone that focus, she was confronted with two more pressing challenges: a scandal involving her former mentor, Salmond, and the global coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 pandemic that would thoroughly disrupt life in Scotland and the world in 2020. The bad blood that resulted between former allies Sturgeon and Salmond deeply divided the SNP as it headed into the important elections for the Scottish Parliament in May 2021, in which Sturgeon and the SNP hoped to gain an outright majority that would allow them to push forward with a new referendum on independence, popularly referred to as “indyref2.” In late March Salmond formed his own political party, the Alba Party, for the election, and Sturgeon witnessed a drop in her popularity. Perhaps more important, opinion polling that had been indicating a growing preference among Scots for independence now showed roughly a 50-50 split between those who preferred independence and those who favoured continued union. All these developments unfolded against the backdrop of the pandemic, to which Sturgeon generally reacted more cautiously than Johnson did.

Both the U.K. and Scottish governments imposed lockdowns on March 23, 2020, following the World Health Organization’s declaration that the outbreak had become a global pandemic, but Sturgeon removed restrictions more selectively than Johnson after the first wave of the pandemic receded, and she re imposed them more quickly than Johnson did when the second wave began swelling in the last quarter of the year. As a result, Scotland fared better proportionally than England did in terms of cases of the coronavirus and deaths related to COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus. While politicians and pundits did not universally approve of Sturgeon’s handling of the public health crisis, public opinion polling revealed that a large majority of those surveyed did. The bounce in popularity that the SNP hoped to carry into the May election, however, was undermined by the Salmond scandal. When the votes were tabulated in the parliamentary election, the SNP added one seat to the total it had won in the 2016 election, but, with 64 seats, it was still one seat shy of an outright majority. Knowing that she had the support of the Green Party (winner of 8 seats) on the issue of independence, however, Sturgeon indicated that she would renew the push for indyref2, despite Johnson’s opposition. But she said that before the issue of the referendum could be foregrounded, the coronavirus had to be tamed.

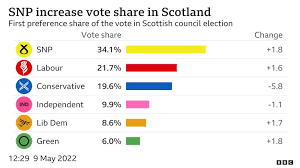

The SNP victory in the 2022 Scottish local government elections is truly record-breaking. Not only is this the 11th national win for the SNP in a row, but it is the greatest-ever result in a local election, winning the most seats won, and with the most gains out of any party. The SNP are the largest party in the highest number of councils. It was also the best-ever result for pro-independence parties. When the final results were tallied across Scotland’s local authorities, the SNP won 453 seats, with the Labour Party managing their second worst performance in half a century, far behind on 282. Meanwhile, the Tories dropped calamitously to 214, the Liberal Democrats were miles back on 87 and the Greens on 35. A second referendum (commonly referred to as indyref2) on independence from the United Kingdom (UK) has been proposed by the Scottish Government. An independence referendum was first held on 18 September 2014, with 55% voting “No” to independence. The Scottish Government stated in its white paper for independence that voting Yes was a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to follow a different path, and choose a new and better direction for our nation”.Following the “No” vote, the cross-party Smith Commission proposed areas that could be devolved to the Scottish Parliament; this led to the passing of the Scotland Act 2016, formalising new devolved policy areas in time for the 2016 Scottish Parliament election campaign. However, the SNP had said before the 2016 election that a second independence referendum should be held if there was a material change of circumstances, such as the UK leaving the European Union. The SNP formed a minority government following the election. The “Leave” side won the Brexit referendum in June 2016. 62% of votes in Scotland were opposed to Brexit. Then in 2017, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon gained approval from the Scottish Parliament to seek a “Section 30 Order” under the Scotland Act 1998 to hold an independence referendum “when the shape of the UK’s Brexit deal will become clear” and sadly Brexit has been a disaster for not just Scotland but for the whole of the UK. Then in January 2021, the SNP stated that, if pro-independence parties won a majority in the 2021 Scottish parliament election, the Scottish Government would introduce a bill for an independence referendum. The SNP and Scottish Greens (who also support independence) won a majority of seats in the election and entered government together under the Bute House Agreement. In June 2022, Sturgeon announced plans to hold a referendum on 19 October 2023. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson rejected Sturgeon’s request. The question of whether a referendum can take place without the UK government’s agreement has now been referred to the Supreme Court by the Lord Advocate, as it is unclear whether the Scottish Parliament can unilaterally legislate for an independence referendum. We still await their decision

NOTE – Part of Nicola Sturgeon’s recollection of Indyref1

The referendum of September 2014 changed Scotland – and I believe it transformed our country fundamentally for the better.

As the campaign progressed, the whole nation was a hive of debate and discussion of the kind that I have never heard or witnessed in my political career, before or since.

Indyref1 was an invigorating experience, one that saw Scotland come alive, not just with impassioned debate, but alive to the possibilities of the kind of country we could be, contributing in our own small but significant way to making a better world. That might sound lofty and idealistic, but it perfectly captures the spirit of 2014.

It was a campaign in which I crisscrossed Scotland, speaking to people in community centres, town halls and in any number of one-to-one conversations with people in all parts of the country.

There are some moments which stand out in particular. And, as is so often the case, it was sometimes the smaller, apparently insignificant details that linger in the memory, rather than recollections of the big set-piece events like conferences, TV debates and stump speeches.

One of those moments, which stays with me to this day, is a conversation I had with a man one day in the final weeks of the campaign. It was on a street corner in Glasgow, and the topic he was keen to discuss wasn’t the latest football chat, or what had been on TV the night before – he engaged me in a detailed discussion on the finances of independence, and in particular the issue of who would be the lender of last resort after a Yes vote. That conversation and so many others like it were replicated many times over, up and down the country, in the months, weeks and days leading to September 18th 2014.

Scotland was at that point arguably the most informed, engaged and intelligent electorate anywhere in the democratic world. I can hardly think of a better testament to the transformative nature of the referendum, or indeed a better legacy to flow from it.

For the fact is that, while the campaign of five years ago may slowly be starting to fade into history, the passion it brought to our national debate remains as vibrant as ever.

The referendum wasn’t just something which made people interested in politics and in the potential of independence – it was something which made many who had never voted, or who hadn’t done so for many years or even decades, come out and have their say on the day.

That brings me to one of my other abiding memories. It was on polling day, again in Glasgow where I spent much of the latter stages of the campaign that I was spotted by a man at my local polling station. He came over to me, gave me a box of chocolate biscuits and thanked me, simply, quietly but emotionally, for being given the opportunity to vote for independence. It was the first time he had ever exercised his right to vote. It was a small moment on a big day, but it is a memory that lingers and one that says so much. Indeed, the sight of the empty box – the contents had been eaten by hungry activists – had me in tears when I saw it in the campaign office a few days after the vote.

More than half a decade on from that campaign and the question of Scotland’s future burns as brightly and urgently as it ever did.